- Home

- Noreen Riols

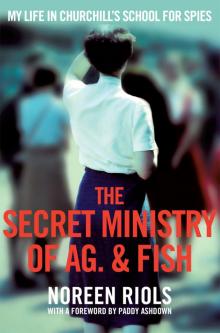

The Secret Ministry of Ag. & Fish Page 7

The Secret Ministry of Ag. & Fish Read online

Page 7

More than half the planes making night sorties over occupied France arrived safely back at Tempsford or Tangmere between four and six in the morning, depending on what part of France they were coming from, and also the time of year. Ideally, they had to have crossed the Channel, away from German flak, before dawn. But they often arrived in a dreadful state, the plane’s undercarriage riddled with bullets, the wings torn half off, having suffered terrible damage on the return journey. Sometimes the pilot managed to land but the plane burst into flames as soon as it touched down, imprisoning him in the cockpit. The passengers sat at the back of the plane and were able to leap to safety. There was always an ambulance and a rescue team at the airfield, but if the rescue team did not manage to pull the pilot to safety, he was burnt alive. Even if the team did manage to haul him out of the cockpit, he was often horribly burnt and so terribly disfigured he was barely recognizable, since it was usually his hands and face which were exposed to the flames. Plastic surgery was in its very early stages during the war. Although Dr Archibald McIndoe, one of its pioneers, did his best and often worked wonders with terribly mutilated flesh, I’ve seen young pilots with hands which were nothing more than claws, and faces which no longer existed: merely a piece of skin dragged between the ears, with two holes for the nose and a slit for the mouth and eyes – without the protection of eyelashes – peering out. The goggles the pilots wore usually protected their eyes to some extent, but even so some pilots were blinded. Yet when they had taken off from that very airfield only a few hours before they had been healthy, handsome young men with their whole lives before them. Now their ‘normal’ lives were virtually over, and many were so disfigured they were no longer able to live in society and spent the rest of their lives making poppies for Remembrance Day in one of the Star and Garter or Cheshire Homes.

Out of the 329 high-risk landings and pick-up operations by plane organized by SOE, 105 failed. 161 Squadron made 13,500 sorties into occupied Europe, and in France alone landed 324 agents and picked up 593. There were in total 600 casualties among their air crews, whose effective strength was 200. So between 1943 and 1945 the force was literally wiped out three times. And 138 Squadron had considerably more sorties to their credit – with corresponding losses. It is almost impossible to imagine the scale of the SOE’s clandestine operations, let alone the huge losses inflicted upon the Special Duties Squadrons.

Chapter 4

After working in Montague Mansions for a while, I was transferred to Norgeby House. The main building was teeming with people, representing every occupied country. It was by no means a quiet life, but at least it wasn’t as hectic as my days with the Crazy Gang. On the surface, there appeared to be some kind of order. We had a much closer contact with the agents, whether they were departing or returning from the field or setting off to begin their long training. And I soon became very well acquainted with the whole process.

Every returning agent was given a huge breakfast at the airfield on arrival and then immediately taken to Orchard Court, a luxurious block of flats in central London, for a Y9, the codename for a debriefing. They were usually able to give very valuable information about what the conditions were really like behind enemy lines.

SOE also had another flat along the Bayswater Road, less well known in the Section than Orchard Court. We used to take the bus to go there, a tuppenny-ha’penny fare, which dropped us right outside the door. I have heard that agents who were under suspicion were kept under lock and key there, as well as Germans who said they wished to defect to the Allies and join SOE. Escaped prisoners were supposedly interrogated there, too. I never attended any such interrogations, but I was told that there was one foolproof question the interrogating officers posed to any prisoners they suspected of being German spies: what was meant by the phrase ‘a maiden over’. It was deemed that such arcane cricketing terms would only ever be identified by a true Brit. Another was to enquire whether they knew the name of Buck’s dog. Every agent had met Buck’s faithful companion, which accompanied him to the office every day, and would certainly have remembered its name. Unfortunately, after so many years, that is a detail I cannot remember!

SOE occupied the whole of the first floor of Orchard Court, and the people living in the other apartments going about their everyday business hadn’t the remotest idea – I doubt they even suspected – what was going on under their very noses. The French agents jokingly nicknamed Orchard Court la maison de passe (the brothel)! It was anything but! More like Clapham Junction, with people coming and going non-stop in every direction. Arthur Park, a lovely man, was the major-domo or butler – I don’t think he had an official title. He was in charge of the flat and, for security reasons, had the difficult task of keeping agents of different nationalities apart. Not always easy since often there were agents leaving for various countries, all clustered there together, while waiting to be collected by their conducting officers. But Arthur held a trump card! Orchard Court had a black marble bathroom – with a bidet, which was an unheard-of appliance in England at the time. Today no one would bat an eyelid at the bathroom’s exotic design, but in those far-off wartime days a black marble bathroom was the height of eroticism. And everyone wanted to view it for themselves. So should he have a collection of agents leaving for different countries all at the flat at the same time, Arthur would shut them in separate rooms, after promising to personally give them a tour of the famous bathroom – if they behaved. But that if ever they escaped to take a peep for themselves they would not be allowed even a glimpse, and would have to leave with their curiosity unsatisfied. I became very popular in the Section because I had actually seen the black marble bathroom, so my company was often sought by those eager to learn the details.

Arthur was a middle-aged Brit who had lived most of his life in France but who, after Dunkirk and the fall of France, had had to leave his French wife and hurriedly make his way to England to serve King and Country – only to discover on arrival that he was too old for active service. He was perfect for his job at Orchard Court, however: very firm, but very gentle. I remember telling him so and asking him why he had been chosen. ‘The General [Colin Gubbins, the head of SOE] told me it was because I knew how to keep my mouth shut,’ he replied, smiling. He had a lovely smile. And it was that smile which departing agents carried with them, since Arthur was one of the last people they saw before leaving. And one of the first persons they saw upon their return.

One afternoon in the early 1960s I was in Paris helping with a Toc H tea party for elderly British residents when the organizer came over to where I was busily buttering scones: ‘There’s a gentleman here who says he knew you during the war,’ she announced. ‘He’s sitting at that table over there. Would you like me to bring him to meet you?’ It was Arthur. To the astonishment of the other helpers and, I imagine, most of the other people in the room, we fell into each other’s arms, delighted to meet up again. After the war, when he was demobbed, Arthur had returned to his French wife, whom he had left in Paris in 1940. But sadly, not long after they were reunited, she was diagnosed with cancer and died. They had married late in life and there were no children, so Arthur was now alone. We ‘adopted’ him, and our children became his ‘grandchildren’. Before he died he spent many happy Christmases with us. We used to collect him on Christmas Eve and take him back to his little flat on Boxing Day. I think that after the noise, the excitement and the hustle and bustle of our family festivities he was happy to collapse into his old armchair by the window looking down into the courtyard . . . and sleep.

Sitting in on the debriefings and witnessing the different reactions of the returning agents was a revelation. Some came back with their nerves shattered, their hands trembling uncontrollably as they lit cigarette after cigarette. Yet others who appeared, to me at least, to have lived through much more harrowing experiences returned completely relaxed, behaving as if they had just spent a fortnight lying on a sea-lapped tropical beach soaking up the sun.

One agent had been th

e organizer of a réseau in Normandy. His radio operator had been killed, and he had sent an urgent message to London requesting an immediate replacement. Although every agent learned something about wireless communications, it was only the basics, and without the pianist he was cut off from any substantial contact with HQ. I don’t know whether trained radio operators were in short supply at the time, or whether there was some other explanation, but London sent in a man who didn’t speak French. It was a disaster. He was a danger not only to himself, but to the whole réseau. The organizer, furious, sent a signal to London saying ‘Send me a Chinese next time,’ to which London replied: ‘Looking for a suitable Chinese.’ Perhaps understandably, the organizer returned with his nerves in shreds.

But there was another chef de réseau who, although he had been very cleverly evading the Germans for months, had finally been captured. He was arrested, imprisoned and sentenced to death. He was to be executed at dawn the following morning. We were all in despair. He was only twenty-nine, and the father of two young children. The next morning the whole of F Section was silent, without its usual frantic activity. Suddenly there was a loud commotion. A signal had arrived. ‘He’s escaped and is in hiding, but the Germans are searching for him everywhere and are closing in. The situation is desperate. They won’t be able to keep him hidden much longer. Must send in a Lysander tonight.’

All hell broke loose. ‘Get on to the Air Ministry immediately and tell them we must have a Lysander tonight,’ Buck shouted. The rest of us scattered in different directions to try to find an available plane. I still don’t know why one of the ‘Lizzies’ from our own squadrons wasn’t used. Perhaps they were all already booked for other operations that night. But our crisis coincided with the period during which the RAF was heavily engaged in intensive bombing raids over Germany’s principal towns and cities, organized by Air Marshal Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris. ‘Bomber’ Harris has often been severely criticized for what some considered his ruthless bombing of German cities. His critics seemed to have forgotten that enemy bombers reduced London, Coventry, Hull, Liverpool and other important British towns to a heap of rubble. But the Air Marshal held firm, replying to them: ‘They have sown the wind, so they shall reap the whirlwind.’ But no one dared tell Buck that there was not one plane available for the next two or three nights. Finally his assistant approached him with the news.

‘I don’t want a bomber,’ Buck exploded. ‘I want a Lysander.’ As I mentioned, Buck could be very choleric and often blew a fuse, and when he did, it was best to keep out of his way. Yet as quickly as he boiled over he simmered down. ‘Oh, get hold of the Yanks,’ he said at last. ‘They won’t let us down.’ They didn’t. That night at ten o’clock there was a Dakota on the airfield waiting to take off, manned by an experienced pilot, all set to pick up his ‘Joe’.

The following morning the rescued agent arrived at Orchard Court to be debriefed. He was as cool as a cucumber. It was impossible to even imagine the nightmare he must have lived through, yet he seemed to have taken it all in his stride and showed no immediate signs of stress or ‘nerves’ after his terrifying experience.

In 1944, another agent found himself in the same situation. His return was less dramatic, but his arrest and escape were remarkable. Francis Cammaerts, codenamed ‘Roger’, had been a schoolmaster and a pacifist. As a conscientious objector at the outbreak of war he was sent to work as a farm labourer. When his younger brother, an RAF fighter pilot, was killed during the Battle of Britain he was so incensed at his brother’s untimely death that he laid down his pitchfork and joined the Army. Cammaerts’s father was a famous Belgian poet, and he was bilingual, so he was approached by SOE, trained and parachuted into France.

The Gestapo had also been searching for ‘Roger’ for several months. He remained one step ahead of them until, through a stupid mistake, they finally tracked him down. They arrested not only ‘Roger’, but also two other agents who were with him at the time, a considerable coup for the enemy and a massive blow for SOE. All three were imprisoned in an impregnable fortress and sentenced to death, with the executions set for the following morning. Once again the whole of F Section was in despair. We knew them all and, apart from the personal anguish, the loss of three important agents at once was devastating. The following morning the Section was again like a morgue. You could have heard a pin drop when once again there was a loud commotion. There had been another last-minute miracle, and a signal arrived announcing their escape.

It had been orchestrated by their amazingly courageous and audacious courier, Christine Granville, with the help of a large sum of (fake) money parachuted in by SOE from North Africa, combined with a great deal of persuasion and many threats from Christine. She also managed to persuade one of the senior prison officers to help her. He had realized that the war was almost over, that the Allies were advancing and taking village after village and that it was to his advantage to be on the Allies’ side now that Germany was doomed to defeat. The three agents, together with Christine, who had been waiting for them a short distance from the prison, were driven to a point just outside the Allied zone. From there they drove themselves to a neighbouring town in time to join in the festivities celebrating its liberation after the German retreat. The liberated agents did not immediately return to London, but when after a few months they arrived in the office they too appeared, on the surface, to have suffered no ill effects from their terrifying experience.

Once the war ended, Francis Cammaerts settled down with his wife and young family and resumed his teaching career without, on the surface, having any dire repercussions from his close brush with death. He said afterwards that, during the night before his scheduled execution, he didn’t remember feeling any particular fear, merely a sense of regret. He thought, ‘What a pity,’ and left it at that. But who knows what after-effects he may have suffered without showing any outward sign of stress or pain? We only see the face people wish to show us. The mistake is to think that an outer calm represents what is going on inside. Many agents carried with them inner scars for a very long time, some for ever.

Recently I met ‘Roger’s’ eldest daughter, Joanna, and asked her about her father. ‘Roger’ had died at ninety, and, after his wife’s death a few years earlier, Joanna had cared for him. ‘I heard that he was very restless,’ I ventured. She looked surprised but assured me that his restlessness was due to the fact that, as he gradually rose to the top of his profession, it had involved the family moving a great deal, at one point spending several years in Africa. But that as far as she could see he hadn’t appeared to have had any serious after-effects as a result of his wartime experiences. ‘He drank a lot,’ she smiled. ‘But then they all did. And,’ she added with a twinkle in her eye, ‘he was a great womanizer.’ ‘Roger’ was extremely attractive: I was not surprised that women fell for him like ninepins. ‘My mother was a wonderful woman,’ Joanna ended. ‘She understood him, and they had a very happy marriage. When she died a few years before he did, my father seemed to go to pieces and lose interest in life. He adored her right till the end.’ ‘Roger’ has now almost become a legend, and his story is very ably told in Clare Mulley’s recent book The Spy Who Loved on the incredible life and adventures of his Polish courier, Countess Krystyna Skarbek, alias Christine Granville.

Attending those Y9 debriefing sessions, I grew up . . . fast. When I was recruited I had been a happy-go-lucky, starry-eyed teenager with, so I thought, the world at my feet. But, listening to the often harrowing stories of these returning agents, some of whom had lived closely with death, torture and betrayal and yet were not very much older than I, and some of whom were shattered by their experiences, brought me down to earth with a bump. Witnessing their courage and devotion to the task in hand, one could not help but be affected. It changed me almost overnight from a starry-eyed girl into a woman: and perhaps prepared me for the suffering which later I myself was to encounter. I slowly came to understand and to accept that life is made of hills and valleys, highs

and lows and that suffering is part of it. Everyone suffers at some point in life. No one escapes. Some suffer more than others and there doesn’t appear to be any reason why. I also learned that torturing oneself in an attempt to find an answer or a reason for this seeming injustice is the road that leads to madness. There is no answer. I wonder if this questioning of why some suffered while others escaped was not the beginning of my search for a meaning to life, and the road which led me to faith.

Until the war I had been sheltered, protected from the blows and buffetings which daily life inflicts. I hadn’t questioned the whys of suffering because I had not experienced it: my questions about life began during the Y9s, where I was face to face with men and women who had suffered both mentally and physically and survived. So when my turn came, remembering their different reactions, I realized that it is the way a person reacts to suffering which shapes them and forms their character. I could either let the pain dominate me and make me bitter, or I could use the pain to my advantage, learn from the experience, albeit a painful lesson, but through it grow and become a more rounded, more mature person. Watching these returning agents’ reactions and hearing their stories I realized that people are not jellies; they cannot be poured into a mould, left to set then turned out – all equal. We are individuals with our individual characters, and sensitivities. And some are more resilient than others. I learned not to judge, certainly not by outward appearances, and not to criticize, but to accept people as they are.

Those Y9s gave me a mental picture of what it was like to live in an occupied country, showed me what many were enduring under the Nazi jackboot: and I realized how very near we had come to being an occupied nation. Their often down-to-earth recounting of their experiences gave me a great insight into the terrible psychological strains and pressures the agents were subjected to. Their life in the field was a journey through fear and darkness, often treachery, and they lived with great loneliness. Even before their departure, and certainly once back in England, they were isolated. They could tell no one outside the small F Section circle what they were doing, share with no one but us their doubts, their anxieties, their fears. I also realized that, in order to carry out their difficult missions, courage was not enough. They needed more than the quick burst of adrenaline required for a ‘hit and run’ mission; they had to possess a special kind of courage: a cold-blooded nerve which endured for days, weeks, sometimes months, even when doubt and exhaustion almost overwhelmed and drowned their spirit. They needed endurance and, usually, a passionate belief in a cause. Living so near the edge of death, they were more aware of life than the rest of us are. Many of us tend to take life for granted. They didn’t.

The Secret Ministry of Ag. & Fish

The Secret Ministry of Ag. & Fish