- Home

- Noreen Riols

The Secret Ministry of Ag. & Fish Page 24

The Secret Ministry of Ag. & Fish Read online

Page 24

Now, looking back, I understand why my engagements always ended in disaster and heartbreak. The men were wiser, more far-sighted than I. They realized before it was too late that I was marrying a ghost, that I was using them as a substitute for the man I had lost and never forgotten, and they didn’t want to be loved in that way. They wanted to be loved for themselves, and at the time it was something I was incapable of doing. I not only made myself very unhappy, but I also made them unhappy. It was some years before I discovered that love had been there all the time. But like so many things which are under our noses, I didn’t realize it.

I had met Jacques in February 1946 shortly after he had been demobilized from General de Lattre de Tassigny’s First French Army, for which he had volunteered in June 1944 after the Allied landings in Normandy. One afternoon, when I walked into the News Room, he was sitting at a typewriter, hammering away with two fingers. We became friendly, but not more friendly than I was with a lot of other people at the time, and although I enjoyed his company, he was more interested in me than I in him. I wasn’t romantically interested in anyone at the time, and I don’t think I had any wish to be. He invited me to Paris to visit his parents and then to holiday with the family in the south-west, where his grandmother had a farm.

I shied at the thought. I was quite happy with the idea of going to Paris, but for me a farm in south-west France meant an old peasant woman with no teeth, wearing clogs and a black apron, spreading grain for the hens. The thought of perhaps being asked to get up at dawn and help swill out the pigs did not appeal. So I refused. Had he told me that his grandmother’s ‘farm’ was a vast wine-growing estate where all the family, uncles, aunts and cousins gathered in the summer, I would have been more enthusiastic. But in spite of my lukewarm response to his attentions, when he left the BBC the following year to work for the United Nations at Lake Success we kept in touch through Christmas cards.

Through a meeting at a party, I was offered the chance of going to Bucharest, then very much behind the Iron Curtain – Stalin was still in power – to teach in a small school for diplomatic children who were too young to go to boarding school in England. I protested that I knew nothing about teaching, but was assured that it was all done through a correspondence course. So I accepted the challenge and found it very interesting. On my return, as I believed at the time, to London I decided to stop over in Paris, where my brother was on a course for the Army. It was quite an experience travelling from Bucharest to Vienna – I think the train only went once a week, and Romanians had to leave it at the Hungarian frontier. Only the one carriage, that day I travelled, carrying the two British Queen’s messengers, the Swiss courier, the Israeli ambassador and me was allowed to proceed. It took ages to cross the frontier into Hungary, which at the time was also under Russian occupation. While we waited, guards high up on lookout posts had their machine-guns trained on us in case any unauthorized person had concealed himself in the train in an attempt to cross the border and escape, hopefully to freedom. The formalities took at least an hour, during which time our compartments were turned upside down by Russian soldiers. It was frightening. The two Queen’s Messengers, who were in the next compartment to mine, asked me to join them, which made me feel a little more secure. They also fed me, since I had brought no food for the journey. There was none to be had on the train, but since the QMs made the journey once a fortnight, carrying the diplomatic bags back and forth, they were prepared and had a primus stove and all the equipment necessary for preparing makeshift meals.

We went through the same hair-raising performance all over again on reaching the Hungarian border with Austria, where the train was halted, in the middle of the night, in a kind of no man’s land before being allowed to cross the frontier and enter Austria. I think that halt was even more dramatic than our experience at the Romanian/Hungarian border, which had been carried out in daylight. Unfortunately, on the night I travelled, while the train was waiting in Budapest station, a man had inserted himself between the rails underneath the train in an attempt to escape to freedom. He was discovered by the soldiers doing the search and tried to make a run for it. We were unaware of this until suddenly, while our wagons-lits were being literally turned upside down by the soldiers searching perhaps for more fugitives, several shots rang out, and I imagine the person attempting to escape was killed. By the time the train finally got on its way and shunted into Vienna I was suffering from violent stomach cramps, brought about solely by nerves. The journey had certainly been an experience, one I don’t think I shall ever forget. Nor shall I forget the feeling of relief, almost exhilaration, I felt when we finally crossed the frontier and entered freedom.

But our troubles didn’t end there. We were caught up in an avalanche outside Salzburg and nobody, not even the British embassy in Paris, seemed to know what had happened to us. Geoffrey went backwards and forwards to the Gare de l’Est on false alerts all day, and, finally, when the embassy telephoned him at one o’clock in the morning to say that the train had been located and would be arriving in an hour, he asked Jacques, who had a car, to accompany him to the station. When the train finally arrived, at two o’clock in the morning, four days after leaving Bucharest, they were both at the station to meet me. My trunk had disappeared in the avalanche so, in the hope that it would eventually reappear, I stayed on for a few days in Paris. By the time it did arrive I’d caught German measles!

It was April, a magical time in Paris. The air was like champagne, and I was condemned to view through the open window of a fourth-floor flat the heady spring and the young couples gazing into each other’s eyes and exchanging kisses as they strolled entwined along the banks of the Seine. I was sitting up in bed, covered in spots and feeling very sorry for myself, when a friend I had known at the BBC came to visit and commiserate with me. She was now working at a press agency in the rue de la Paix and told me she was looking for an assistant. She offered me the job, and, being at a loose end, I accepted, only returning to my parents’ home to sort out my affairs. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was never to live in my home country again.

When I returned to Paris, Geoffrey had already left to rejoin his regiment. I had visited the city only once before, for a few weeks in 1949, so I didn’t really know my way around: but Jacques was there, and we renewed our friendship. He was endlessly helpful and seemed to be always available for me when I needed advice or assistance, and I came to rely on him.

He found me accommodation and coped with the mountain of paperwork necessary at the time in order to get temporary residence status. He even joked that, rather than wading through this lot, it would probably be easier to marry him and thereby obtain French nationality, a solution which would solve all my problems. I laughed and took it as a joke, but I realize now that he was only half-joking: he was in fact ‘testing the waters’. After a while he did ask me to marry him, but I hesitated. Scenes of my previous engagements, and the pain, not only that I had endured, but that I had also inflicted on others, flashed through my mind, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to repeat the experience. I liked Jacques enormously and had come to rely on him. I enjoyed his company and was grateful to him for all his help. But was that enough?

Jacques assured me that it was enough, and that he could make me happy. I was still a selfish beast and didn’t consider whether I could make him happy. I was only thinking of my feelings, and again I hesitated. But perhaps, after all this time, something was melting inside me and, in the end, I realized that I did love Jacques. It was not at all the love I had expected. In my search for some wild passion, I had hoped to recapture the blinding feeling of adoration I had experienced during the war with Bill. I had not considered the simplicity of the union of two souls. In Jacques’ company I no longer felt alone. I felt complete. Now, looking back, I can see more clearly what attracted me to Jacques. He is not unlike Bill in so many ways: quiet, unassuming, courageous, amusing, not easily ruffled, and he gets on with everyone, the qualities Bill possessed. One of my husban

d’s favourite sayings, which I have now adopted, is: ‘Any fool can fight. It takes an intelligent person to keep the peace.’ I gather from that that he must be very intelligent, since he refuses to quarrel with anyone!

But my heart had been dead for too long for it to instantly spring back to life, and I was troubled with doubts. I was, after all, no longer a starry-eyed teenager rushing blindly into marriage; I was a mature woman who saw the pitfalls not only of marriage, but of marriage with someone from another culture, and I found myself wondering about the wisdom of the step I was about to take. I imagine most women have these same doubts at the prospect of sharing their lives, their most intimate moments, with another human being – in my case someone whose upbringing had been diametrically opposed to mine and who, by nature, was so different from myself.

I am impetuous, impatient, critical, inclined to judge and also to act first and think afterwards, often with disastrous consequences. Jacques is calm, unhurried, optimistic, seeing only the glass as half full, not half empty, as I am inclined to do. He looks only for the good, and usually finds it, in others. In the more than sixty, nearer seventy, years since February 1946, when I first met him, I have only twice seen him lose his temper, which I imagine must be a record. How could two people so fundamentally different, not only temperamentally, but also culturally, ever merge into one whole, I sometimes asked myself in the weeks leading up to our wedding. It was impossible. And yet we have achieved the impossible, largely thanks to my husband’s forgiving spirit, and also perhaps because we share the same faith, proving that the old saying ‘couples who pray together, stay together’ is true.

Jacques is not at all the kind of man I had expected to marry. The four men I had been in love with had all been military types who towered above me, had blond hair, blue eyes, bristly moustaches, medal ribbons lined on their chests and enjoyed balls and parties. Jacques is the opposite. He is scarcely half a head taller than I, though with the advancing years he seems to have shrunk a few centimetres, with the result that we are now running neck and neck. I have never seen him with a moustache, though I know from photos that he did sport one briefly during the war. His dark-brown hair, once wavy and so abundant it used to flop into his eyes, is conspicuous by its absence, and his gentle hazel eyes are now hidden behind glasses. But his smile is still the same, that smile which so captivated my mother when she first met him and prompted her to exclaim, ‘He’s like a little boy!’ He was twenty-six at the time and a hardened veteran of the First French Army!

Jacques can’t dance, except on the toes of his partner, and he is not keen on parties, although he always accompanies me when we are invited; and he is not in the least bit interested in decorations. He can’t even remember where he put the Croix de Guerre with Bar which he was awarded on the field whilst fighting in Germany towards the end of the war! I only found out he had the medal when, before moving from Paris, I was turning out a drawer and came across it. He laughed when I asked him why he had received this award. ‘I chased the Germans out of France all by myself,’ he teased. ‘Didn’t you know?’ And he has never elaborated further.

He hates what he calls ‘fuss’, with the result that our wedding was original to say the least. We got married in the lunch hour! Well, Jacques’ lunch hour. I’d stopped working two days before. It would have been unthinkable in the 1950s for an executive’s wife to have worked outside the home. Jacques chose the date, bang in the middle of August, when absolutely everyone has fled to the coast for les grandes vacances and Paris is empty . . . of Parisians. My parents were staying at my brother’s house in Connemara at the time and offered to come over for the occasion, but I told them not to bother. Being the kind of people they were, they didn’t insist but took me at my word. Jacques’ parents were in the family house in Narbonne for the vendange (grape harvest), where we later joined them. So we were a wedding party of four.

When my witness – an old Sandhurst friend of my brother who was in Paris for a few days on his way to Korea – and I arrived in the church porch, only Jacques’ witness was there waiting for us. The bridegroom hurtled in, breathless, with about twenty seconds to spare. At the end of the simple ceremony the vicar said, ‘Well, at least you can have the “Wedding March”’, climbed up into the organ loft and played it himself. As we four marched, as solemnly as we could, down the aisle of this vast, echoing church with its 600 empty seats, we all suddenly saw the funny side of this bizarre situation and were overcome with helpless giggles.

Once in the porch, Jacques said, ‘Sorry, I have to rush, I’m terribly busy at the office,’ and disappeared into a taxi. So Hugh took Anne and me to tea at Rumplemeyer’s, after which he tactfully dropped me at the entrance to the block of flats, saying: ‘I expect Jacques will come home early and take you out for a celebration dinner.’ It was only after he left that I realized Jacques had forgotten to give me the key to the flat. My frantic calls to his office were met with the stern reply that Monsieur Riols had given orders that he was not to be disturbed on any account. It was August and the concierge, who had a spare key, was on holiday, so I sat on the stairs outside the flat until nine o’clock that evening, when the lift disgorged my weary husband. He smiled at me, said, ‘Weddings are exhausting, aren’t they?’ and collapsed on the bed in a comatosed sleep.

A few years later my brother married: a sumptuous affair with pages and bridesmaids, over 300 guests and a splendid reception to follow in his in-laws’ garden. As the last guests drifted across the lawn to say goodbye, I collapsed onto a seat under one of the trees, enjoying the relative peace of this gentle April evening after the hectic past few days. My father came across and sat down beside me. ‘I wish we had been able to give you a wedding like this, dear,’ he said sadly. Remembering the exhaustion etched on the faces of my brother and his bride when they left on their honeymoon, I turned to look at him in horror, and exclaimed emphatically, ‘I don’t.’

My sister-in-law turned out to be the sister I had never had, and the four of us became great friends. My links with my brother, which had strengthened after the tribulations he had put me through during our early years, never lessened. I could always call on him when needed and know that he would be at my side, an invaluable asset when, in his early fifties, Jacques was rushed to hospital with cardiac arrest and suffered a coronary thrombosis. Christopher, our youngest child, was only nine at the time and I did not know where to turn. Suddenly Geoffrey was there, with his wife’s blessing, coping with everything and almost carrying me through what proved to be a few traumatic weeks. I knew he would never let me down. But in the end he did. Three days after his seventy-fourth birthday he died. It was a terrible shock to us all. And the only time he didn’t keep the promise he’d made to me some years before. I had been indignant after my mother-in-law’s funeral at what I considered to be the offhand way in which the pallbearers had slung her coffin between them as they walked down the aisle. And I voiced my anger . . . loudly.

‘I’ve got sons and nephews,’ I said, ‘when I die I want to be carried on their shoulders, reverently. I don’t want to be waved about like that!’

‘Don’t you worry, old girl,’ my brother soothed. ‘I’ve organized many pallbearers at military funerals. I’ll be there to see you are properly carried.’ And I felt appeased. Now he wouldn’t be there. But when he died what hit me most, I think, was the realization that, as far as our English family was concerned, I was now alone. Our last cousin on our mother’s side had died the year before, at only sixty. Since he had never married, there were no nieces or nephews left to remind us that he had ever lived. My father had been the youngest of four children, so all our Yorkshire cousins were in their teens when I was born and had long since died. I was now the only one left: the sole survivor. It was a strange feeling. We had never been a close family, our links were very tenuous, but all the same, it was odd to think that whenever I went to England there would be no one to welcome me. It was then that I realized how lucky I was to have married into th

is close-knit French family, bristling with cousins and aunts and uncles who had all welcomed me wholeheartedly.

When Jacques and I married a whole new world opened up, and I was finally able to put the past behind me and start again. I feel so blessed when I hear other women complaining about their mothers-in-law, some with good reason, because I was so lucky with mine. Jacques’ mother welcomed me, the ‘foreigner’ her son had married, with open arms, and once we were married I immediately became part of his large extended family. Jacques seemed to have cousins who were so far removed they were vanishing into the distance, who whenever we met always greeted me warmly with ‘Bonjour, Cousine,’ and a kiss on both cheeks. Being a part of this united family I had married into, so different from my reserved, one might almost say cold, English relations, I at last found the love and the security which, perhaps even without realizing it, I had always craved.

I had been brought up by parents who were kind, but remote. They themselves had been raised in the late Victorian era, when to show any kind of emotion in public was simply ‘not done’ in polite society. And they continued the tradition with my brother and me. Cuddles and spontaneous hugs were shows of affection I never experienced as a child. How different and how much better things are today. When I see my grandchildren being showered with love by their parents I understand how, during my own childhood, without even consciously realizing it, I must have missed the warmth and the wealth of affection my children give their offspring. They are so much wiser than I was. My children understand that, ‘done’ or ‘not done’, human beings at every age need love; and they also need roots.

When I married Jacques I ‘adopted’ Narbonne in the Languedoc, the pays in south-west France, near the foothills of the Pyrenees, where Jacques’ father’s family had been landowners since the thirteenth century: and finally I began to put down roots. I was born in Malta so never felt I had any roots in England and, my father being in the Royal Navy, I had never felt ‘rooted’ anywhere, since we moved around a great deal. My mother always complained that the curtains never fitted the windows in the next house. I have in fact inherited a trunk full of curtains which she collected over the years, always hoping that one day she would move into a house where the windows and the curtains matched each other; but I don’t think she ever did. My father’s base was Portsmouth, and my brother was born there, but although we had a house in Southsea, we only lived in it very briefly, and it was eventually sold.

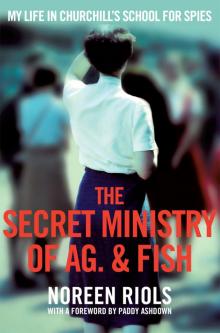

The Secret Ministry of Ag. & Fish

The Secret Ministry of Ag. & Fish